A Natural Law Critique of the Communist Manifesto

This is a research paper submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the course DR38405, Worldview and Ethical Theory at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (Kansas City, MO) on April 15, 2023.

Introduction

Natural Law is a philosophical perspective concerning morality and ethics that essentially states that there are certain issues of ethics that are common amongst all mankind and can be found through human reason.[1] The concept of natural law is summed up in the idea that there are simply certain moral concerns that all mankind in their right minds will agree upon regardless of their culture, socio-economic background, or upbringing—such as the issue of murder, the individual rights of a person, and even the responsibility of local, regional, and national government. If the theory of natural law is correct, then the most logical conclusion is that no one has any justification for breaking certain moral or ethical laws because these certain laws are common amongst all men.

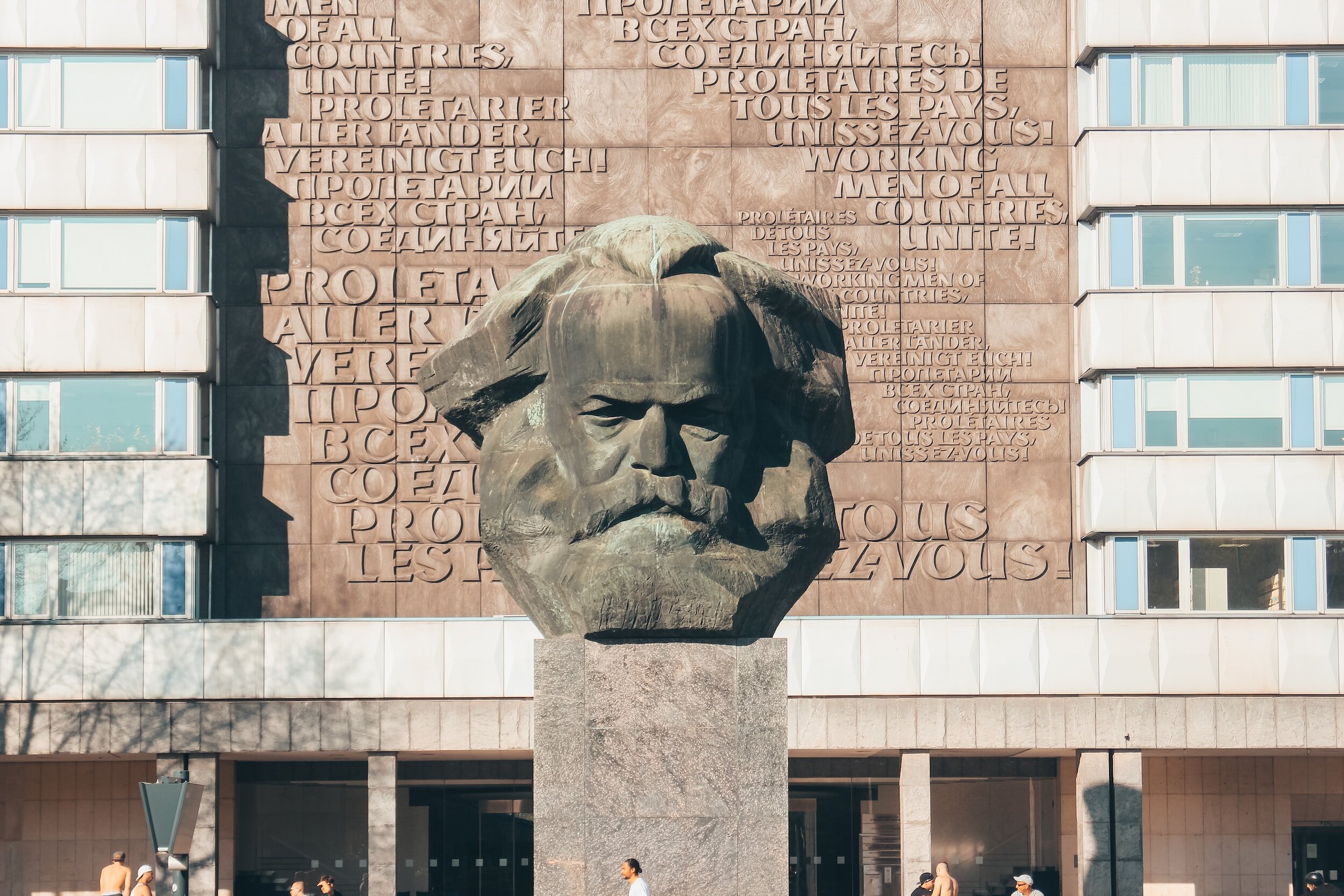

The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels is a political document written in 1848 in which the theories of the proletariat are espoused and disseminated. Engels and Marx write about the struggle of the proletarians against the bourgeoisie as the bourgeoisie owns the means of production and lords their ownership of capital over the proletariat. The primary premise of The Communist Manifesto is that the proletariat has to “sell themselves piecemeal” and “are a commodity”[2] Or in other words, whereas the bourgeoisie reap the benefits of owning all the means of production, the proletariat are slaves in a system that utilizes them as nothing more than another means of production. The proletariat are utilized and seen as a dispensable part of production just like the machinery used for production. Marx and Engels argue that this is a result of and consequence of the industrial revolution and that as the technology increases, the disparity between the proletariat and bourgeoisie continues to grow.[3]

From a cursory survey of the two systems of thought, it might seem as if there is some compatibility, but ultimately the commonality between the two systems is vastly overweighed and overshadowed by the differences between the two systems. The core doctrines of communism differ from the core doctrines of natural law ethics in their ultimate goal, their understanding of epistemology, and how culture and society should interact with their core teachings. Ultimately, neither system can work in accordance with another.

Natural Law Arguments against The Communist Manifesto

The key tenants of communism include the ideas given in the introduction concerning the proletariat and the bourgeoisie and the growing disparity between the two people groups. In addition, Marx and Engels write at length about the need to not just understand this disparity, but to equalize the two people groups by the abolishing of private property,[4] the end to religious thinking,[5] and the monopoly of the state over production, transportation, and banking.[6] The key tenants of natural law ethics include the ideas given in the introduction concerning the ability of mankind to come to a common consensus concerning right from wrong, the ability of mankind to come to this consensus through reason, and in the case of Christians who espouse a natural law ethic, the fact that sin causes great difficulty in determining right from wrong.[7] In addition, natural law ethics essentially argues that if the individual was to reason accurately and fairly, he would determine what is right from wrong by nature and would not necessarily need any sort of special revelation for the bulk of ethical decisions.[8] Clearly the two systems of thought have many contrasting ideas including their epistemology, the primary issue at hand, and how one should solve the ethical dilemmas of mankind.

Concerning epistemology, the two system offers differing ideas. For instance, The Communist Manifesto really does not deal with epistemology, but rather assumes that the issues at hand have always been and continues to worsen as society continues to industrialize. In other words, Marx and Engels assumes that the issues plaguing society between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat are readily evident to anyone and that the issues themselves have been worsening throughout time as the world continues to industrialize. Natural Law, however, does deal with epistemology in that it asserts that moral right and wrong can be determined through human reasoning. Or, in other words, when people utilize the reason already innate to them, they can discern right from wrong and wrong from right. For a Christian espousing natural law, the natural sense of right and wrong is then built on by means of special revelation.[9]

Concerning the primary issue at hand, the two systems again differ. The Communist Manifesto bases all issues on the tension between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Marx and Engels essentially argue that every issue in society finds its root in the disparity between the two people groups and how they treat one another because of that disparity. Natural Law ethicists would argue that the primary issue at hand is sin because through sin, the natural law becomes obscured. Budziszewski writes, “A law was written on the heart of man, but it was everywhere entangled with the evasions and subterfuges of men.”[10]

Both systems, then, have to deal with how each system answers the need to solve their main arguments. For the natural law ethicist, the primary issue at hand is to determine the best way to explain the commonality of certain ethical principles to individuals that may or may not believe in a common law. If the natural law ethicist is correct in the assertion that all men have a common understanding of certain moral or ethical principles, but many have experienced subterfuges due to sin, then the primary concern is to explain natural law ethics to individuals who do not believe that there can be a common natural law. For the communist espousing The Communist Manifesto, the primary issue is the disparity between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Because the assertion is that the primary issue is the disparity between the two people groups, the only means to fix the issue is through political control over the situation. Or, in other words, because the issue is that of who has control in society, the only answer is to shift control from private persons into the public’s control. Thus, private property is abolished, individual ownership is abolished, and power, authority, and the means of production are centralized within the state itself.[11]

Conclusion

In conclusion, though both systems readily admit that there are significant issues in society, where each system originates their ideology differs and what they consider to be the primary issue at hand differs. Or, in other words, The Communist Manifesto assumes that every problem can be solved through political means, whereas a natural law ethicist assumes that the primary issue is the sinful state in which mankind lives, which warps their understanding of right and wrong; and the only way of solving the issue of sin is through Jesus Christ. The primary critique of The Communist Manifesto from a natural law perspective is simply that The Communist Manifesto attempts to fix symptoms of an underlying problem, whereas the natural law ethicist focuses intently at the root of the problem through understanding morals and ethics that are common to all people.

[1] Gifford Andrew Grobien, “The Natural Law and Christian Ethics,” Logia 29, no. 1 (2020): 7.

[2] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto, (San Diego, CA: Booklover’s Library Classics, 2021), 34.

[3] Ibid., 35-36.

[4] Ibid., 53.

[5] Ibid., 66.

[6] Ibid., 69-71.

[7] J. Budziszewski, What We Can’t Not Know: A Guide, (San Francisco, CA: Ignatius Press, 2011), 4-5.

[8] Ibid., 230-234.

[9] Norman Doe, Christianity and Natural Law: An Introduction, (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 217-219.

[10] J. Budziszewski, 4.

[11] Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, 69-71.